Netty Test Practice Report

Netty Test Practice Report

[TOC]

Introduction of Netty

Netty is a high-performance network application framework with asynchronous event-driven APIs that enables developers to focus on business logic, instead of low level details like synchronization, manual management of ByteBuffer. Simply put, Netty > java.nio + java.net.

Netty vs java.net: async and event-driven

By leveraging callbacks, Netty implements a event model for network communication. User can register listeners to events and operations, and get async notification of the completion status of those registered handlers.

Also, Netty eliminates the need for tedious synchronization by allowing only one thread to handle all the I/O operations and events within a EventLoop.

Those coming from other programming languages like JavaScript would find this practice very similar to async frameworks like Koa: accessing a global ctx from self-defined callbacks, and then easily attach them to different places.

Netty vs java.nio: ByteBuffer for everyone

Comparing JDK’s ByteBuffer to Netty’s Bytebuf, Netty mainly improved two issues: API friendliness and performance.

- No ease of use:

- once it’s instantiated, its capacity cannot be extended;

- only one index for both reading and writing;

- no

forEach, user has to do bound checking every time.

- Performance and GC overhead

- writing a heap-based

ByteBufferrequires copying the memory to direct buffer before passing it to JNI - Netty manages direct buffer directly.

- Netty uses reference counting for more real-time efficient GC

- writing a heap-based

Beyond nio and net: Extensibility

Separate of concerns: Using React model, Netty guides developers to separate business logic from the implementation of the application.

Netty also has built-in support for self-defined protocol application development.

Netty has extensive support for application layer protocols including UDP, TCP, HTTP(S), and even self defined ones. User could also attach the serialization library they like (e.g. Protobuf, Thrift).

Project statistics

Lines of Java code: 481,008. Get the LOC using below command:

1 | git ls-files | grep -E '.java' | xargs wc -l |

On GitHub there are currently 28.5k stars and 14.1k forks. The project is still under active development.

Building the project

It requires JDK 8 and Maven 3.8.1 or below to build. Run mvn package to compile the jar file. Skip the test using mvn package -Dmaven.test.skip. If you experience errors with checkstyle, you could also skip it using the -Dcheckstyle.skip option. Replace those options by -D"[option]"=true when using Windows PowerShell.

As a framework that deals with OS-level I/O, it provides additional artifact on Unix platform so that user can gain better performance and GC comparing to the NIO transport provided by JDK. Take Linux as an example, add netty-transport-native-epoll to the dependencies of pom file. Then user could use these features by simply importing the respective special classes if they already have the corresponding JAR file.

Existing test cases

Netty uses JUnit5 for testing, Mockito for mocking. During daily development, user can use a special class EmbeddedChannel to mock a Netty connection for testing.

Unit tests are written inside each package. Due to the large amount of test cases, sometimes abstract test classes are created to define common methods to test.

Test suites analysis in terms of functional testing and partition testing

As a type of black-box testing, functional testing derives test cases from the software’s specifications. The whole process involves identifying independently testable features, and then find relevant inputs based on such features. Finally, test cases specifications are formed. Since test writer doesn’t have to know any internal structure or implementation of the software, it could result in reduced developer bias.

After specifications are broken into minimum testable features, the representative values and behaviors for a certain feature becomes clear. Failures are distributed unevenly in the whole possible inputs, so partitioning makes it easier to catch the failures by properly dividing the input space.

There are numerous packages and modules in Netty. Among them, the most important packages are buffer, handler, channel.

Partition example: reference counting feature

Let’s take the byte buff reference count feature as an example. The life cycle of certain objects are managed by their reference counts, so that Netty can return them (or their shared resources) to an object pool as soon as it is not used anymore, improving the allocation and deallocation performance.

It would be helpful to re-iterate the specification of this feature:

- the initial reference count of a reference-counted object is 1

- when

release(), the reference count is decreased by 1 - when the reference count reaches 0, the reference-counted object is deallocated or returned to the object pool

- when the reference-counted object is deallocated, it cannot be accessed again

- buffers derived from a buffer share the reference count of that parent buffer

My partition for it would be:

- newly created

bytebufobject (reference count: 1) bytebufobject that’s being used in several places (reference count > 1)bytebufobject whose reference count is 0bytebufobject derived from newly createdbytebufbytebufobject derived from object with reference count more than 1- derive a

bytebufobject from a deallocatedbytebuf

JUnit cases for this example

The test cases for above situations would be inside a new mode named swe261.

Netty Test Practice Report - Chapter 2

Why finite model

In short, finite model is a representation of the software artifact being described. Due to its properties of being compact and predictive, it can first reiterate the specifications, facilitating better understanding of it[^1]. Secondly, by describing the essential possible executions and state transitions of the software, a finite model could shed light on the problem of “what to test”, and make edge cases more obvious. Finally, since a finite model depicts the transitions of software, it can serve as a visual aid of code coverage, and show the number of cases having been covered.

Functional model example: Netty’s event-based data processing components

Network programming can be ideally modeled via event-driven architecture.

With an event-driven system, the capture, communication, processing, and persistence of events are the core structure of the solution.[^2]

This article chooses Netty’s event-based data processing components as an exemplar of finite model. The nature of events that occur during network communication suits the needs well. First of all, it would be useful to have some preliminary introduction of Netty’s event-based before diving into the testing of the events within it.

Basically, the abstraction of such event model is based on three core classes, Channel, ChannelPipeline, and ChannelHandler [^3]. ChannelPipeline is the container of a set of ChannelHandlers, and a ChannelPipeline is permanently bounded to only one Channel in its life time, and vice versa.

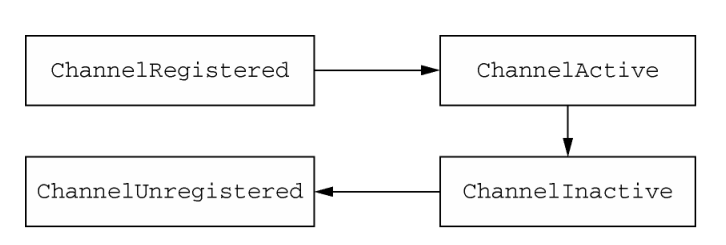

Channel could be roughly thought of as the Socket class in Java’s network programming interface, but with more simpler APIs. In Netty it defines four basic states: ChannelUnregistered, ChannelRegistered, ChannelActive, ChannelInactive. Its status model is as below:

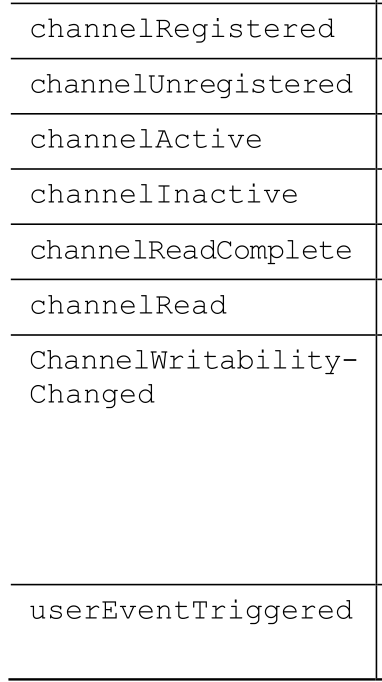

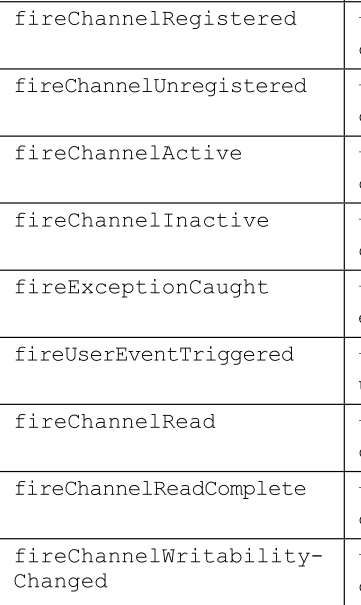

ChannelHandler is the main component of Netty, from an application developer’s point of view.[^3] It serves as a container to store all application logics that are to be applied on the inbound and outbound data. Below are the inbound methods that will be called when status of the Channel instance it’s registered is changed.

Respectively, as its container, ChannelPipeline‘s API publishes events:

In conclusion, as the network data flows, events can be triggered by OS (read and write complete, bind successful), or in special cases be fired manually. Events can be passed on to the next handler along the pipeline, or to all succeeding handlers.

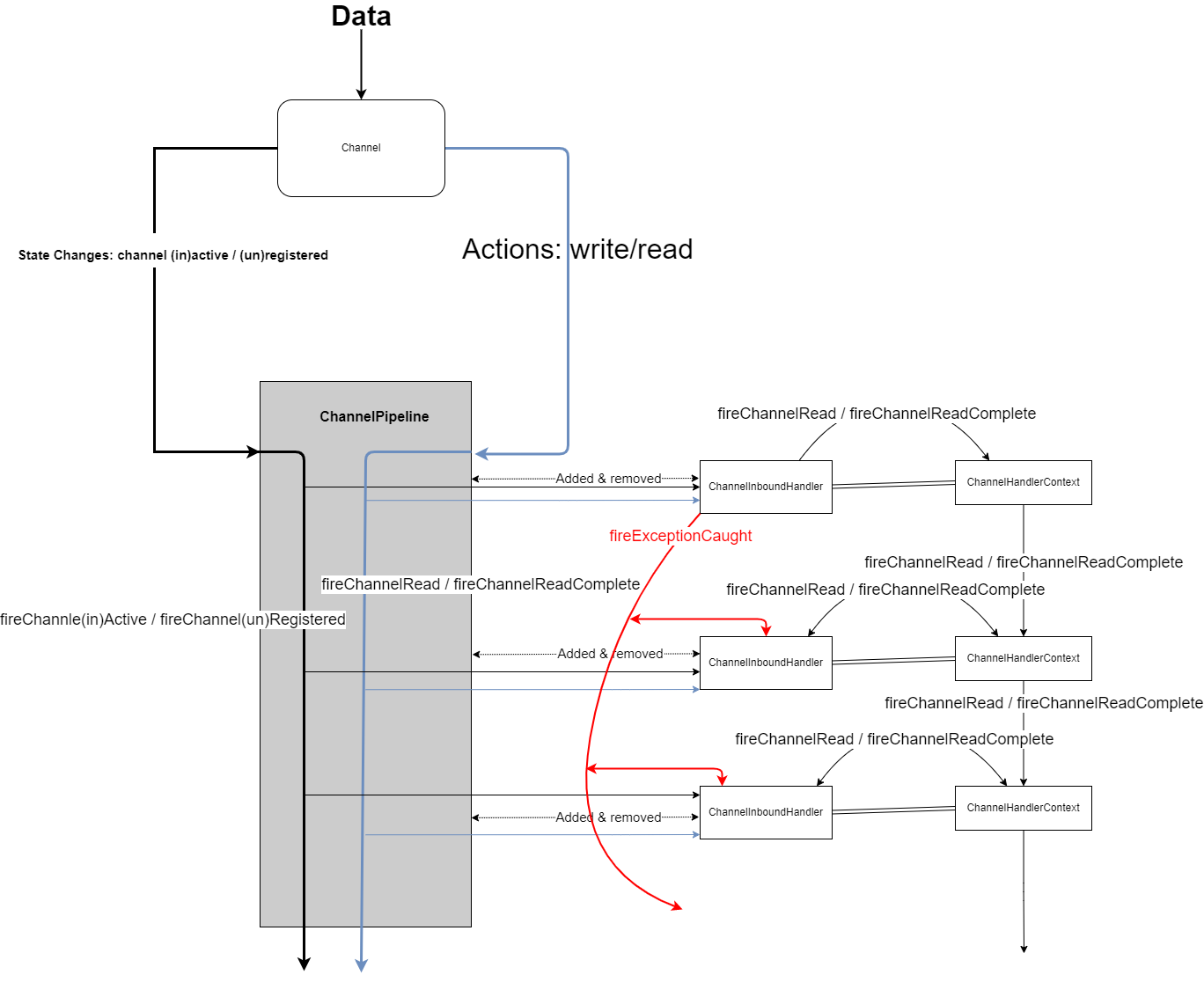

Finite state machine for the inbound components

Below is the illustration of the FSM. The high definition version of the illustration can be found in the GitHub repo with the name finiste_state_machine.png. To make the model more compact for understanding and practical uses, here we only look into the inbound components.

Overall, flow of changes starts from channel, passes through pipeline, and ends at handler. There are two major kinds of events: state changes and data events. When a channel is (in)active, or when it’s registered to a EventLoop, it initiates state changes that will be forwarded to all handlers in the pipeline. Pipeline could also pragmatically fire such events. As the main component that application programmer will deal with, handler could have some code relating to such events for some preparation tasks like connecting to respective databases.

Comparing to state changes, data events (blue lines in the illustration) also forward to all handlers added to the pipeline, but there’s a fundamental difference: the inbound data. The inbound data will be forwarded to all handlers, one by one, along with the data events (read/write). Therefore, although all handlers receive data events, but subsequent handlers only get inbound data from the previous handlers, whether the data is modified or not by their precursors. In the end, the data flows to the end of pipeline, which signifies the end of processing for this data. Such flow of data makes it possible for processing the data in a organized and controllable way. For example, it enables easy implementation of self-defined encoders/decoders and serializer / deserializer. All the programmer has to do is writing them as normal handlers, but only putting them at the appropriate position, usually the start or end of the pipeline. Netty provides pre-defined boilerplate classes like ByteToMessageDecoder for such needs.

While such data flow model seem to have addressed all possible problems for consuming inbound data, Netty also provides a finer-granite control: ChannelHandlerContext. A ChannelHandlerContext is created whenever a handler is added to a pipeline, and will stick to the handler during its life cycle. A context can have only one handler, but a handler can be added to multiple pipelines, and thus having multiple contexts. ChannelHandlerContext has many methods that also exist in Channel and ChannelPipeline, but when it triggers events, the event only propagate to the next handler that can handle the event. This mechanism has at least two advantages because it:

- eliminates the overhead of dealing with events (data) that a handler doesn’t need;

- avoids forwarding events to the wrong handlers.

ChannelHandlerContext represents the interaction between two handlers in a pipeline. That’s why in the illustration, the arrows between contexts also end between contexts; while arrows from pipeline would dispatch the event to every handler and continue all the way to the end. In addition to receiving read / read complete events from the respective context, handler could also fire such event, and forward it to the next handler through the use of context. Therefore the arrows are bidirectional.

There is a third type of event: exception, as the red lines in the illustration shows. Exception could occur in any handler during execution. The exception event would propagate through the pipeline of handlers too, but only those the implements the exceptionCaught method could catch and end the exception propagation. The best practice is to always have at least one handler at the end of pipeline that implements the exception logic.

Test suites for this functional model

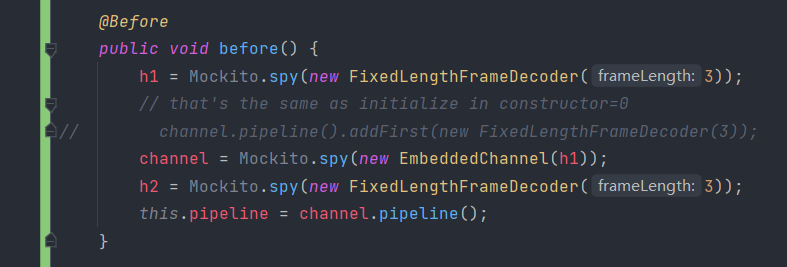

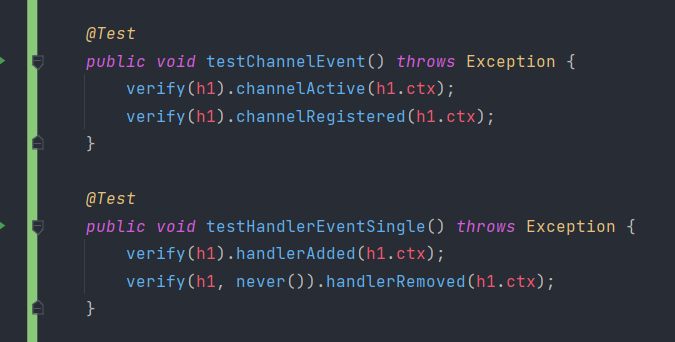

Basically there are three types of test suites to write, corresponding to the three types of events: channel events, handler events, and context events. Here we use Spy in Mockito to test if certain methods are called. The ChannelPipeline class cannot be spied, because it’s a final class.

With Mockito’s Spy function, testing is made a lot easier. Simply several lines could prove that certain methods are called. Those methods could only be triggered due to state changes, so our functional model could be verified.

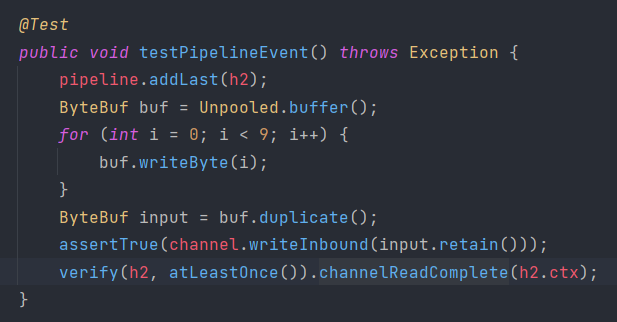

In above code, channel events and handler events are tested. The pipeline event and context event is a little tricky, because it involves simulating real-world network communication. Luckily, Netty provides us with EmbeddedChannel class to conveniently set up unit tests.

The writeInboud method writes data into the channel directly.

References

[^1]: Mauro Pezze, Michal Young. Testing and Analysis, 2nd Edition

Red Hat. Event-Driven Architecture, https://www.redhat.com/en/topics/integration/what-is-event-driven-architecture

Norman Maurer, Marvin Allen Wolfthal. Netty in Action

Netty Test Practice Report - Chapter 3

Why structural testing

Structural testing, also known as white-box testing, is a way of software testing that mainly utilizes the information of a program’s internal structure to design and evaluate test cases. It judges test case thoroughness based on the structure of program itself.

Comparing to specification-based testing, some faults can only be revealed by structural testing. Such faults are often implementation-specific; they are implementation choices made by the programmer that are hardly described by the specifications, like what data structure to use, what SQL statement to execute. Such faults could also be unintentional: memory leak, thread safety, etc.

However, structural testing has drawbacks, too. Even if test cases are thorough from the view of structural testing, it couldn’t guarantee revealing all faults. Covering all control flow elements doesn’t ensure the covering of all possible buggy inputs.

In addition to fault detection, structural testing serves as an indicator of test case thoroughness. For example, the statement coverage criterion requires each statement

to be executed at least once[^1]. Although executing every control flow structure provides no guarantee, a statement never executed / tested is definitely not acceptable.

Test adequacy report on netty-buffer module

As a large, well-developed multimodule project, Netty contains as many as tens of thousands of test cases. It would be practical and insightful to start analysis from a single module first.

Configuration for collecting test coverage data

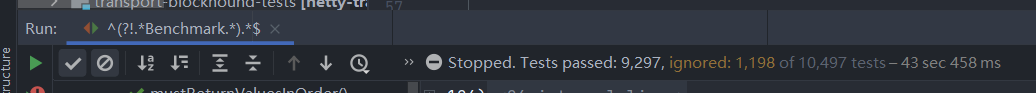

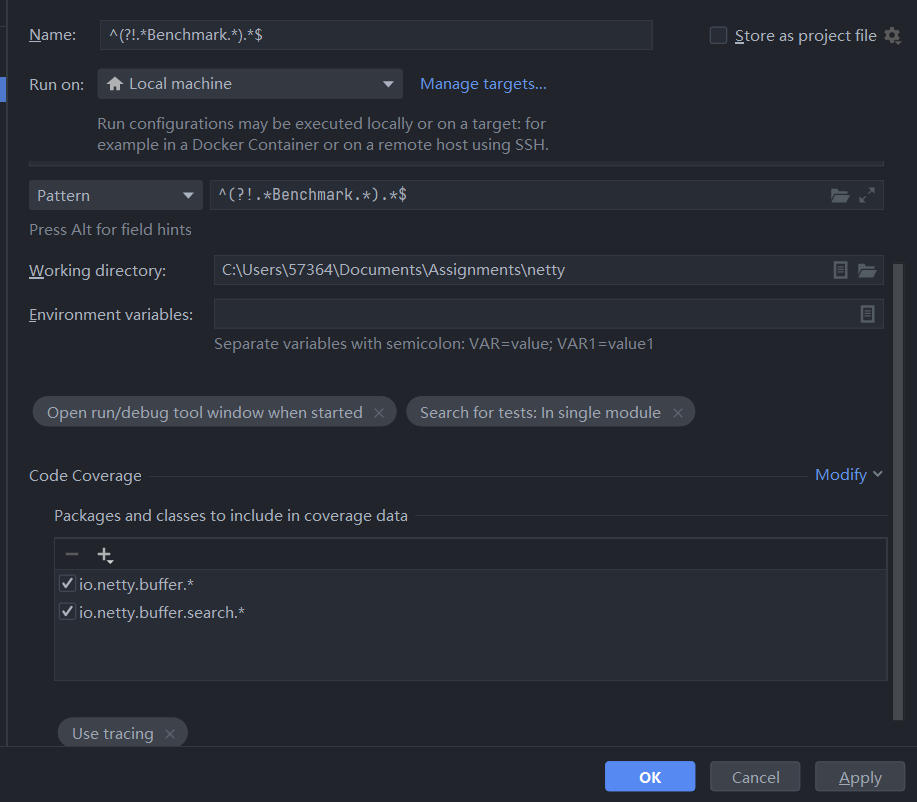

Intellij Ultimate comes bundled with coverage plugin, but there’re several configurations needed. By default, it doesn’t collect branch level coverage, so we need to enable it by checking use tracing option. As with netty, there exist many micro-benchmarks for every module. These benchmarks have nothing to do with testing, and are extremely time-consuming, so a pattern is applied to exclude all tests with a name ending with “benchmark”: ^(?!.*Benchmark.*).*$. Also it turns out that the collect coverage in test folders option is misleading, and would pollute the generated coverage report by collecting test adequacy data for test classes, which certainly would have zero coverage.

Test coverage statistics

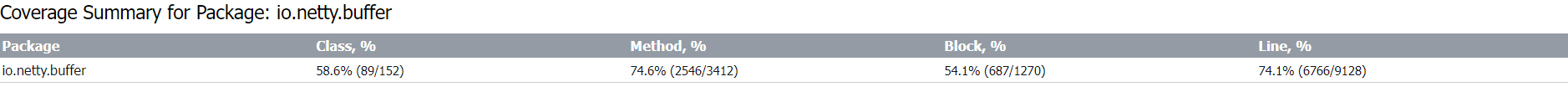

Overall, module netty.buffer is tested well with the majority (75%) of methods and lines being covered.

Line and branch level coverage

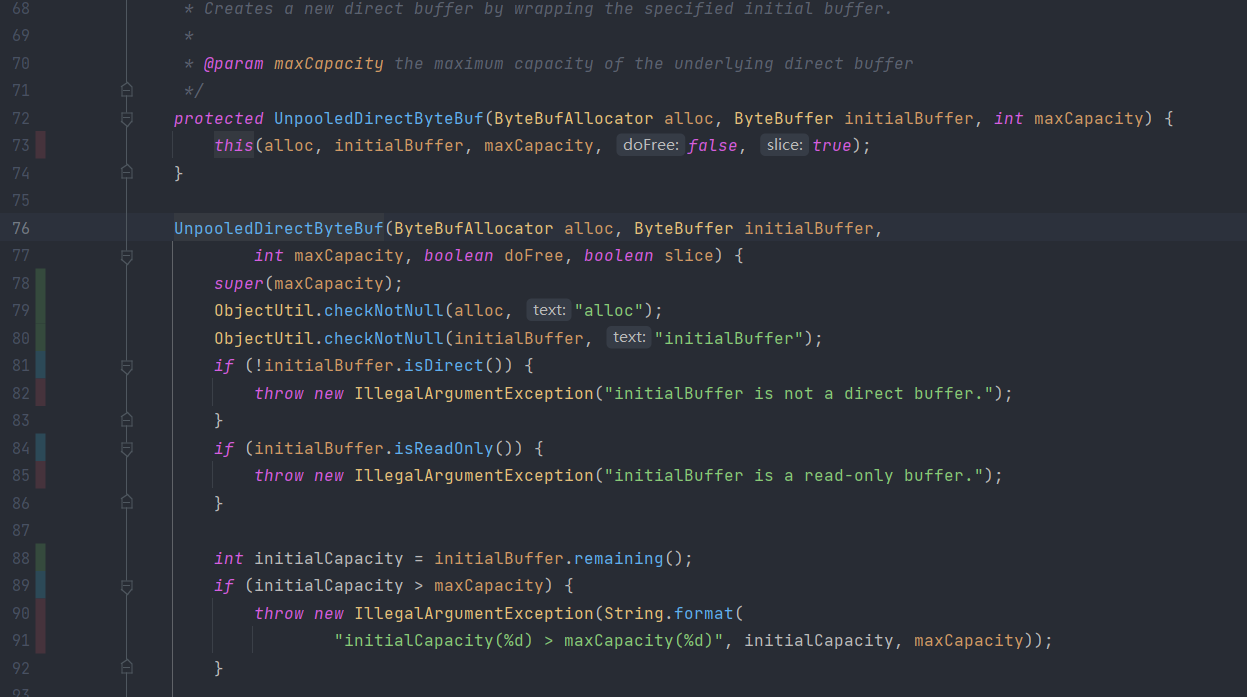

Among the 9128 lines of code, 6766 of them are covered. The uncovered lines often appear to be branches that are not covered; for example, exception statements, as shown below:

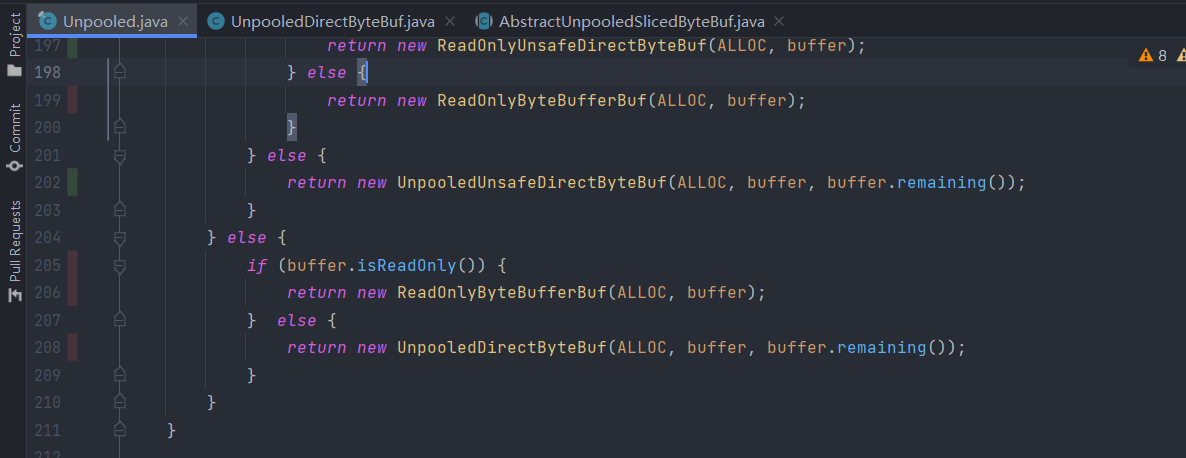

Or just simply untested edge cases:

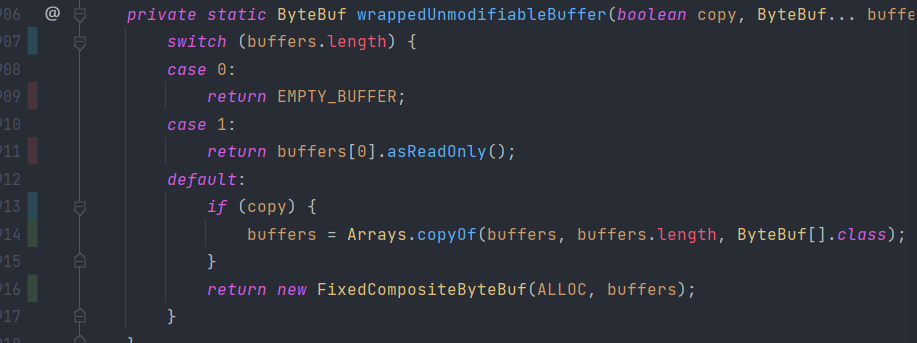

in addition to the common if-else statements, another type of untested branch is switch syntax:

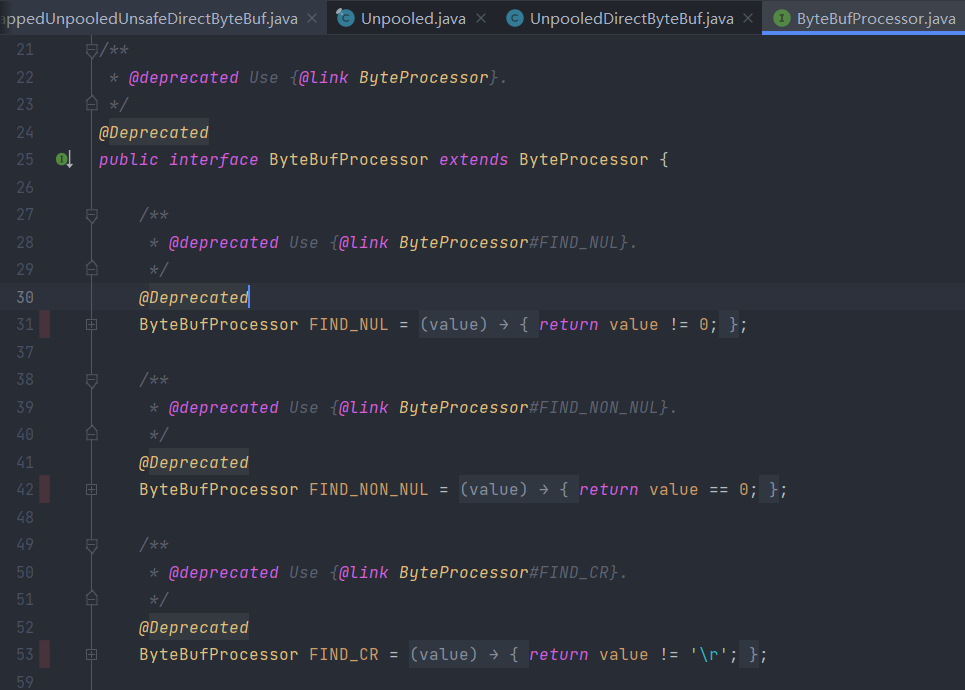

Except for the above reasons, there’re also rare cases, like @Deprecated APIs that are to some degree intentionally not thoroughly tested :

Or untested field of interface:

Method level coverage

But some uncovered lines have no special reasons: they are just not tested as a whole. This should be categorized as method level coverage.

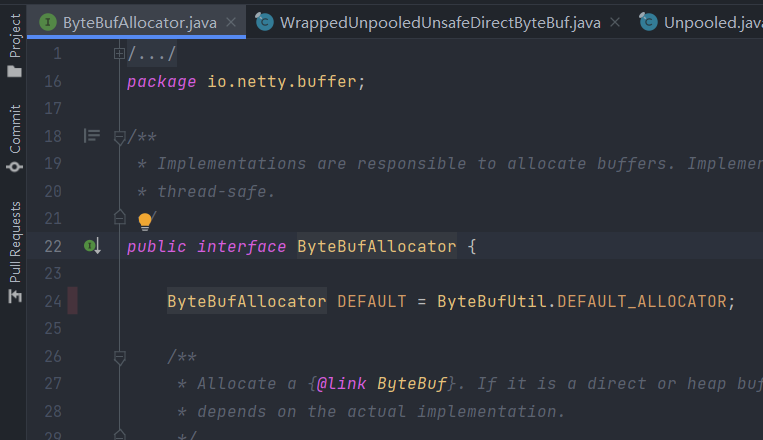

One of the most common properties of the untested methods are protected modifier.

In the above screenshot, class AbstractUnpooledSlicedByteBuf is an abstract class that also extends from another abstract class. We can see that many of its overridden protected methods that are inherited from the upper abstract class are not tested. Such lack of method coverage is somehow reasonable, since those APIs are not supposed to be exposed, as long as their public counterparts are tested, they are guaranteed to work.

But some uncovered lines have no special reasons: they are just not tested due to lack of resource.

Improving test coverage of netty-buffer

Document the coverage before and after

describe the code being covered; describe the functionality being tested/covered

Thanks to analysis above, it becomes obvious what test cases should be written in order to increase coverage. Some test cases I designed would:

cover exception handling like in

UnpooledDirectByteBuf:79;visit uncovered branches like the

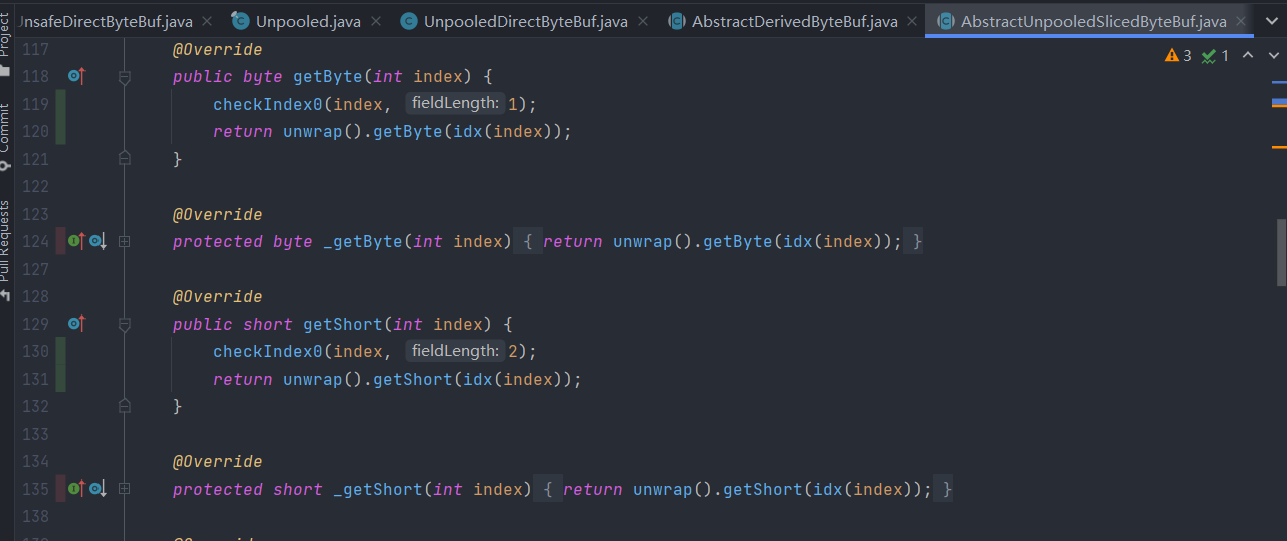

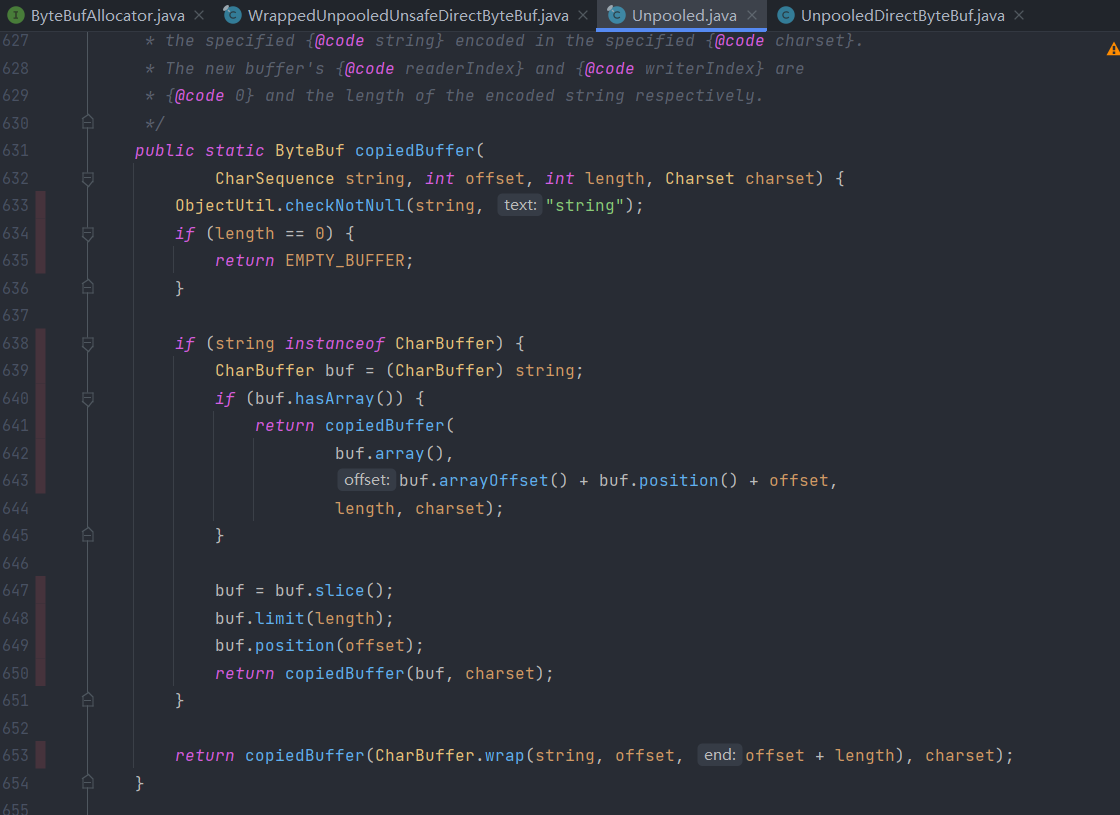

switchin the array function ofFixedCompositeByteBuf, and inUnpooled:907;cover

Unpooled#copiedBuffermethod, line 633.cover the

readBytesandsetBytesmethod for different channels.

Added test cases

In UnpooledByteBufAllocatorTest, different constructor arguments are tested, especially the illegal ones, to ensure that the exception handling for them is working.

On a broader scale, test cases of the readBytes and setBytes methods using ScatteringByteChannel and GatheringByteChannel are added, for all subclasses of AbstractByteBuf class. This could be achieved thanks to Netty’s well-structured class hierarchy of test cases. Adding a test case in the AbstractByteBufTest would result in all its child test classes reusing the case.

Outcomes of newly added test cases

Before adding new test cases, the code coverage at line level for netty.buffer is 6766/9128, meaning that among the 9128 lines of code, 6766 of them were covered. 687 branches are tested, out of all the 1270 branches.

After adding all the new cases, line coverage increases to 6818 lines, and 10 more branches are covered.

References

[^1]: Mauro Pezze, Michal Young. Testing and Analysis, 2nd Edition

Address of the repo

GitHub - rustberry/netty: Netty project - an event-driven asynchronous network application framework

Netty Test Practice Report - Chapter 4

What is Continuous Integration and Why Use it

Continuous integration is a DevOps software development practice where developers regularly merge their code changes into a central repository, after which automated builds and tests are run.[^1]

The core of continuous integration is lies in two practices: merging minor code changes to the code bases, and automated test and deployment. Usually, programmers commit code at least daily. After that, the whole program will be built automatically to incorporate the changes. If building is passed, the program will be automatically tested to ensure that no regressions are added. In the end, the new program artifact is published and deployed, marking the end of a round of integration.

There’re many benefits of practicing continuous integration. From a developer’s point of view, it first frees developers from the time-consuming task of manual testing and deployment. Secondly, bugs are detected at an early stage so that they could be easier to fix. Since continuous integration merges mainline frequently, project managers are able to make better prediction of development time based on the daily progress so far. Product managers could evolve their business strategy more accurately, thanks to getting feedback more quickly from the customers. Finally, users of the product get new features more often.

Why open source project also needs continuous integration

Open source projects often have loose organizational structure, comparing to business entities. Therefore, they are unlikely to have the need to deliver features so frequently, nor do they need to stick tight to the roadmap. They also don’t need to rapidly adapt their business strategy – some may not even have one. Then why is continuous integration good for them?

In my opinion, continuous integration is beneficial at least in terms of development. With automated build and test, maintainers of the project save a lot of time from it. Automated build and test are also quick feedback to guide the commiter who made the code change: he or she could tell immediately if the code change is useful, or if not, what needs to be fixed. That’s why we could often see a project to have a build bot to deal some work of pull requests.

Netty’s Continuous Integration Practice

Netty used to have a self-hosted Jenkins installation that uses docker to run the continuous integration jobs[^2].In December 2020, they switch to using GitHub Actions, which spares them from maintaining a specific host machine. GitHub Actions has large usage limits. Except for better readability of YAML-based configuration (comparing to Jenkins), GitHub Actions also make it more maintainable as the developers could add building configuration files to source control.

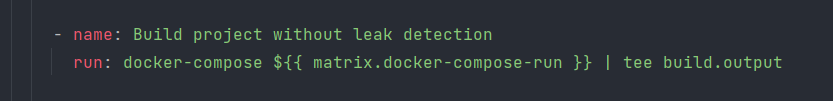

As a framework that utilizes operating system specific features, Netty has the need to get testing on different platforms, and that’s where docker comes in handy. Those docker files are still useful in GitHub Actions workflow. The workflow file can be viewed as an environment setup file; the major work is done in docker compose YAML files. All we need to do is invoke docker commands in the run statement of workflow files, like this:

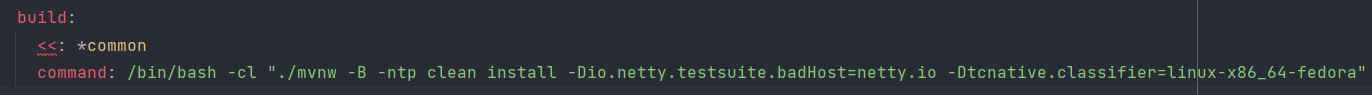

What it truly does is a docker command, in which mvn clean install is executed with various arguments.

Above is the core command in the workflow file. Others define properties of this workflow, environment variables, and so on. Let me explain in detail of the YAML file.

1 | name: Build project |

These lines are at the beginning of the file, defining the name of this workflow, and the trigger to this. On every push to branches main and gh-test (my testing branch), this workflow would be triggered to run. In addition, this workflow is scheduled to run chronologically every week.

1 | env: |

The env entry defines some necessary environment variables to be used during testing.

1 | jobs: |

The jobs entry is the major entry that does the real job. runs-on: ubuntu-late defines that the job runs on GitHub-hosted runners, which is free of charge.

Finally, in steps entry, previously written actions can be imported and reused. Or user can define their own actions with name and run keywords.

Obstacles while practices GitHub Actions

The biggest problem I came across is that Netty project is a big code base, and it takes a lot of time just to run all the tests. Moreover, as a performance framework, it has many benchmarks to run. In average I have to wait for more than one hour for a single workflow run to finish, and then correct any errors detected.

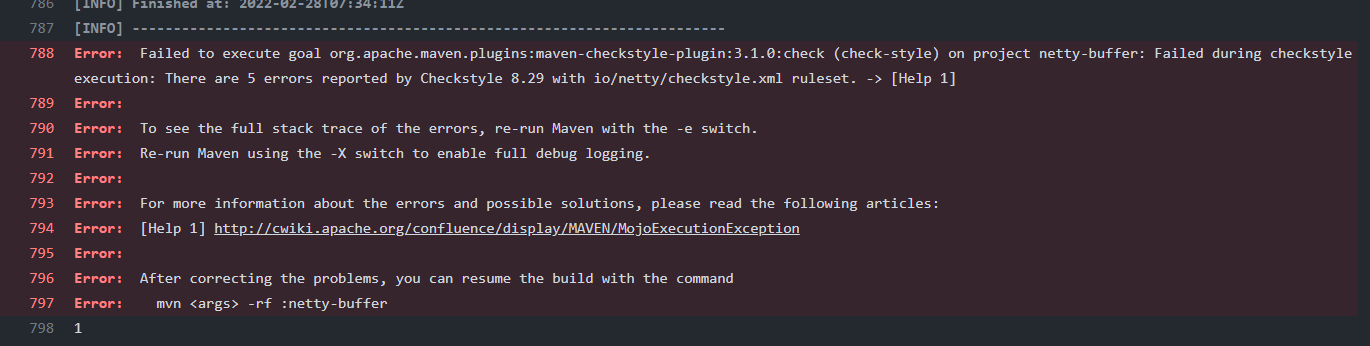

Running maven goals locally doesn’t help since Maven’s CheckStyle plugin seems to have problem with Windows locales. At the start of the report I have been making workarounds to avoid executing its goal on Windows.

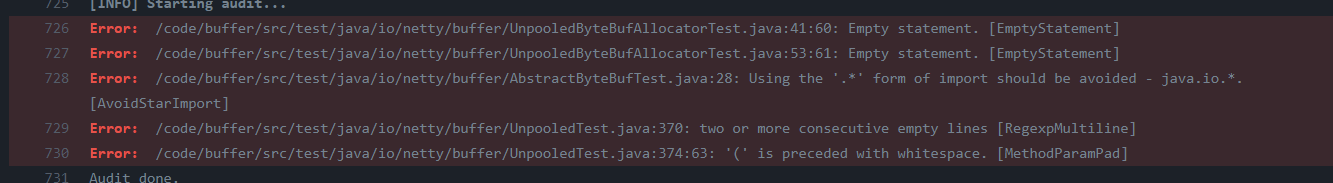

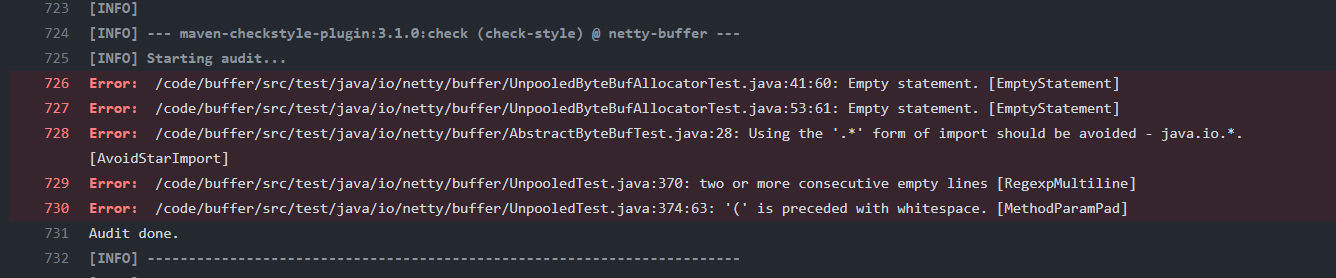

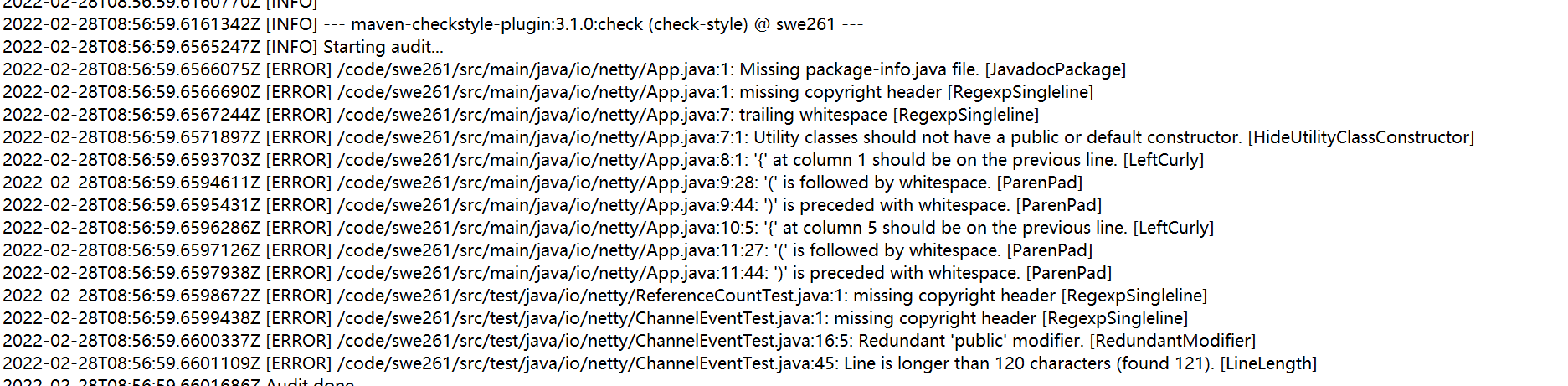

The most frequent errors I encountered are CheckStyle errors. Netty project has its own CheckStyle configurations and code styles; both of them will be checked against during the building process. The newly merged code must strictly conform to the code conventions, not a single space is allowed.

Commit address of new changes

The addresses of the new changes: Merge pull request #1 from rustberry/gh-test · rustberry/netty@c77c6c5 · GitHub

The workflow file being discussed: netty/ci-build.yml at 4.1 · rustberry/netty · GitHub

References

[^1]: What is Continuous Integration?, Amazon Web Services

[^2]: GSoC 2020 Proposal · Issue #10088 · netty/netty · GitHub

Netty Test Practice Report - Chapter 5: Testable Design and Mocking

Definition of testable design and its goals

In its essence, testable design is making it easier for code to be tested against. In Effective Unit Testing, author concludes:

More specifically, testable design makes it easy to instantiate classes, substitute implementations, simulate different scenarios, and invoke particular execution paths from our test code.[^1]

Or in short, testability means:

a given piece of code should be easy and quick to write a unit test against.[^2]

In my opinion, a testable design is also a maintainable design; testable software would also be well modularized. Only modularity could guarantee easy instantiation, easy stubbing and mocking. Therefore, sticking to testable principles is actually something natural when writing code. One may not even need to intentionally make his code testable: as long as one wants to keep the code readable and maintainable, then he/she will naturally write code in a testable way.

There are several principles to conform to. All of them are aimed to solve those testability issues:

instantiate a class;

invoke (test) a method;

observe the outcome at a specific point;

substitute the dependency that the class relies on (so that we could do mocking on it);

override a method (so that method could be mocked, or be delegated to observe its outcome)

Some of the best practices to solve the above issues are:

favor composition over inheritance; avoid complex constructor logic

so that it is easier to instantiate the needed class. It is also good to adapt design patterns like builder and/or factor method if it is really complicated (and necessary) to instantiate.

composition also makes it possible to switch different scenarios for testing by providing different objects for composition.

avoid complex private methods;

- private methods are literally not accessible from the outside of the class, therefore not possible to test.

single-responsibility principle;

- ideally, each function/method should only address one issue. This makes it convenient to observe the outcome, since the data being processed won’t go through complicated changes in such functions.

Testability in some of Netty’s current code

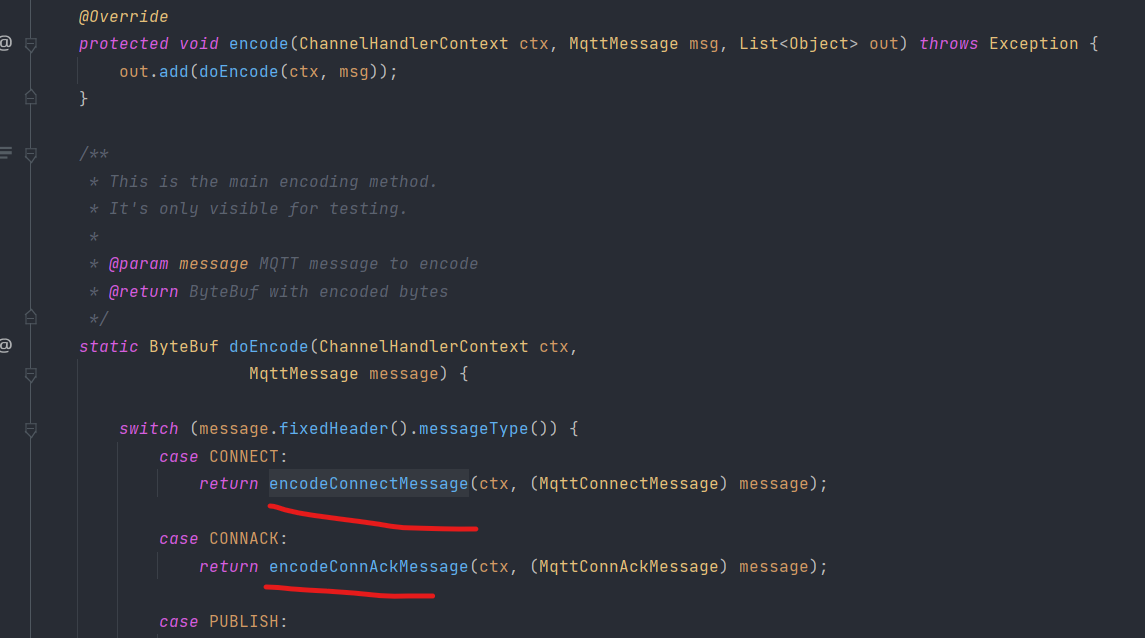

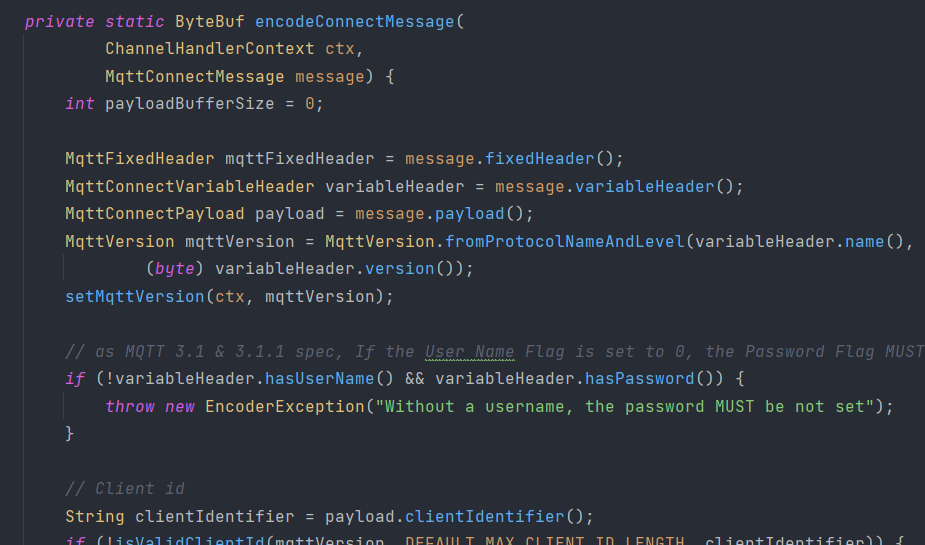

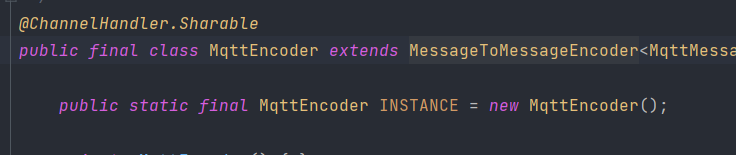

In io.netty.handler.codec.mqtt package, there is a class called MqttEncoder that extends the abstract class MessageToMessageEncoder and only overrides one method: encode. encode is intended to be used to transform the inbound message into another form of message, e.g. from ordinary string to base64 encoded strings. However, this method relies on a set of private static methods to do the actual encoding, as shown below.

This has several drawbacks. First of all, as a private method it’s impossible to write unit test against each of those small private methods to make sure they function well. Secondly, as static methods, they operate on the class rather, than the object, leaving space for possible pollution of data when called by multiple instances.

My way to fix it is to firstly change the modifier to public, and then make sure that any references to variables out side of the scope of this method is thread-safe.

Luckily the only field that might be shared across methods is declared as final. And by checking its usage, it turns out that it is not used inside the class at all, but rather acts as a handler exposed to the outside world for calling. In that case, I think it’s appropriate to keep the methods static, because after all this class is a utility class that is meant to encode / decode messages, and have no internal states.

Mocking and its usage in Netty

Mocking is about generating fake objects that imitate the behavior of the targeted object. The use cases for mocking is when you’re dealing with a complex object (very possibly a third-party object that has little documentation or has complex internal logics) and want to test your own objects’ interaction with it. Interaction testing is different from the more common way of testing: state testing.

Interaction testing is testing how an object sends messages (calls

methods) to other objects. You use interaction testing when calling another

object is the end result of a specific unit of work.[^3]

Basically, interaction testing only checks if certain interactions between objects happened, and does not care about the internal state changes. As the book advises,

Always choose to use interaction testing only as the last option.[^3]

It is often more straightforward to check against values and states, but sometimes only interaction testing is useful. As stated before, when the other objects involved has little documentation and complex internal logic, it is best to leave them intact, and mock a new one to replace them. With mocking, it is even possible to make that third-party object to only have behaviors that are useful for testing.

A mocking example in Netty

Network communication is often hard to set up for testing. For that reason, Netty has already had a convenient class for unit testing: EmbeddedChannel. It can send or receive network messages as the programmer withes. But if one only wants to test their handlers’ interaction with the channel is correct, then mocking is even more convenient.

In fact, the existing test cases for EmbeddedChannel doesn’t use the power of mocking so far. As a Channel, EmbeddedChannel interacts with various complex objects like EventLoop, ChannelPipeline, and ChannelHandlerContext. If our intention is only to make sure that EmbeddedChannel makes correct calls and signals to other instances, then those objects should all be mocked. First of all, this eliminates all the possible “unexpected exception” not originated from our own class itself. For example, EventLoop could become unavailable to assign new threads due to system overhead during testing. More importantly, mocking them helps test designers focus on the purposes of the test cases: test the interaction of EmbeddedChannel. One of EmbeddedChannel‘s responsibility is firing different types of events to different objects to notify them. This is an essential part of Netty’s event-driven flow of data. Therefore, mocking other objects to test EmbeddedChannel is meaningful.

References

[^1]: Lasse Koskela. Effective Unit Testing, Manning Publications

[^2]: The Art of Unit Testing with Examples in .NET, Manning Publications, 2009

[^3]: The Art of unit Testing, 2nd edition

Netty Test Practice Report - Chapter 6

In this chapter, we’ll analyze the code base of Netty automatically, that is, using static analysis tools.

Static analysis tools and their benefits

Static analysis is “a software verification activity that analyzes source code for quality, reliability, and security without executing the code”[^1]. It could also be carried out on the compiled code. Actually we may have all used static analysis before: when we write code in static typing language in an IDE, we could often see intelligent hints like “variable defined but not used”, or “variable written but never read”. Sometimes there could be code branch analysis like “the else statement can never be reached”. Such hints are the results of static analysis; specifically, they are the results of dataflow analysis and control flow analysis. Static analyzers, as the name suggest, are the tools that carry out static analysis on the code.

Comparing to dynamic analysis, static analyzers don’t require actually running the program. Also since it requires no human interference, static analyzers could be an economical way of analyzing a big code base.

Code analysis tools in current Netty project

Dynamic analysis

Netty provides a built-in dynamic analysis feature, leak detection, via class ResourceLeakDetector[^2]. In its essence, ResourceLeakDetector uses JDK’s PhantomReference<T> to track the unreleased buffers in the 1% sample of one’s application’s memory usage, which is a small overhead. A typical example report of memory leak is like following:

Static analysis

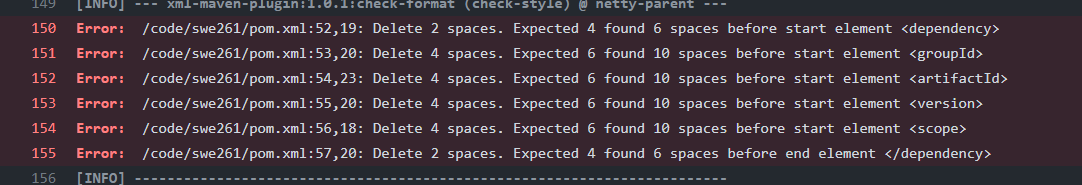

Netty project has its own code style configuration and incorporates CheckStyle as a maven plugin. CheckStyle analysis has been set as part of the goals to be executed during maven building process. It is also part of the continuous integration checks. Commits that doesn’t pass style check would fail during the triggered GitHub Action. Next we’ll see examples of CheckStyle reports on failed runs.

Here’s an example of XML formatting error.

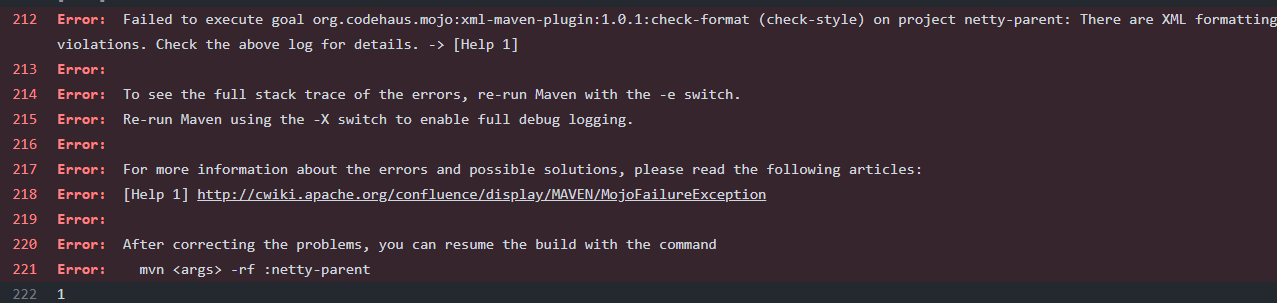

Depending on the configuration file specified, minor errors such as indentation will also be checked. When maven detects a build failure, it would cease all the remaining building tasks for other module and output a brief repot like this:

Another example of report on coding style:

And the summary are as follow:

Breaches of coding conventions are detected according to different coding style ruleset. The total number of errors in a module would be counted.

Code analysis using SpotBugs and PMD

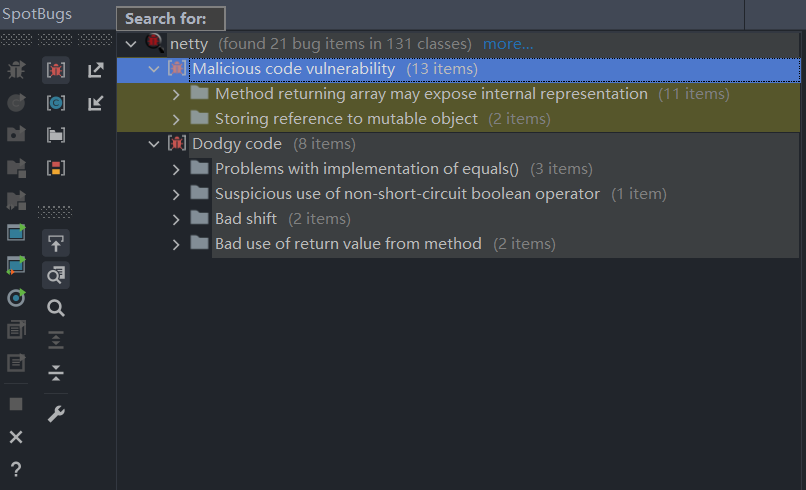

SpotBugs comes handy as a well-developed Intellij plugin, while PMD has different behaviors in terms of the Intellij plugin and the binary version. Since Netty as a multi-module project is too big, we only inspect the buffer module.

Overview of the results

Here let’s look into the aggregated overall results first.

For SpotBugs, it claims to find 21 bug items in 131 classes, excluding the test files.

It generally falls into two categories: Malicious code vulnerability (relating to security) and Dodgy code (relating to coding style).

With PMD, things are little trickier. The standard binary PMD command-line by default outputs ascii text to standard output like below.

For a better format and for a summary of the report, use this command:

1 | .\pmd.bat --short-names -d ..\..\netty\buffer\src\main\java\io\netty\buffer\ -R category/java/errorprone.xml -f summaryhtml --report-file report.html --property linkPrefix=https://github.com/rustberry/netty/blob/4.1/ --property linePrefix=L |

The summary of binary PMD excluding test files is:

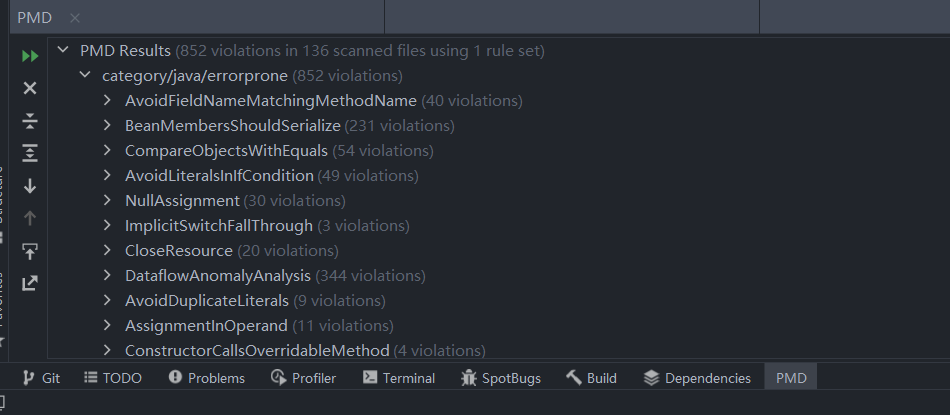

PMD uses a XML form of ruleset that could be customized to analyze the code. The ruleset I chose is errorprone.xml. Altogether it claims to have finds 561 bugs in this module.

However, the Intellij plugin finds different bugs. I suppose there might be difference on the ruleset they use.

The plugin version claims to find more bugs: altogether 852 violations. PMD Intellij plugin has no way to configure target directory to exclude test files, so for the purpose of contrast, I ran the binary version on all files in buffer module. Altogether the binary version finds 791 errors.

All of these three versions of static analyzers don’t show the severity of bugs they find.

Detailed analysis of some important warnings

Findings of PMD

Some of PMD’s findings are not actual problems in the code. Take the CloseResource problem for example. It claims to find unclosed resource in following lines:

1 |

|

In fact, utf8out is a private field of the class, and has a specific method that takes care of the closing of it:

1 |

|

The plugin version of PMD are more paranoid then binary version. For the CloseResource problem, it not only finds “bugs” that binary version finds, but also reports bugs from abstract classes. That should be an unnecessary behavior, because abstract class methods are meant to be overloaded and subject to change.

AvoidDuplicateLiterals is another error that is more an indication than a bug declare. It will report duplicates in annotations:

1 |

|

Or strings in constructors of exceptions:

1 | if (isOutOfBounds(start, length, capacity)) { |

AvoidCatchingThrowable is a good advice, since the scope of Throwable is very broad. Luckily, all the occurrences of such errors in this module are intended, and are located in static initializers of the class; this makes it possible to catch all possible errors during initialization.

1 | try { |

The most useful one I found so far is the ConstructorCallsOverridableMethod warning. Explanation from the PMD website:

Calling overridable methods during construction poses a risk of invoking methods on an incompletely constructed object and can be difficult to debug.[^3]

This rule is also mentioned in Effective Java‘s 18th item: Design and document for inheritance, or else prohibit it:

There are a few more restrictions that a class must obey to allow inheritance. Constructors must not invoke overridable methods, directly or indirectly. If you violate this rule, program failure will result. The superclass constructor runs before the subclass constructor, so the overriding method in the subclass will be invoked before the subclass constructor has run.[^4]

The code that violates this rule:

1 | public CompositeByteBuf( |

class CompositeByteBuf uses the overridable method setIndex in its constructor. Although in its super class’s constructor setIndex is not called, CompositeByteBuf has a sub class that also overrides setIndex, in WrappedCompositeByteBuf class:

1 |

|

So when WrappedCompositeByteBuf initializes, there might be chances that its uninitialized setIndex method is called by CompositeByteBuf.

Findings of SpotBugs

Comparing to PMD, SpotBugs have better IDE integration. The first category of warnings is Malicious code vulnerability, and contains two types:

May expose internal representation by returning reference to mutable object, and

May expose internal representation by incorporating reference to mutable object

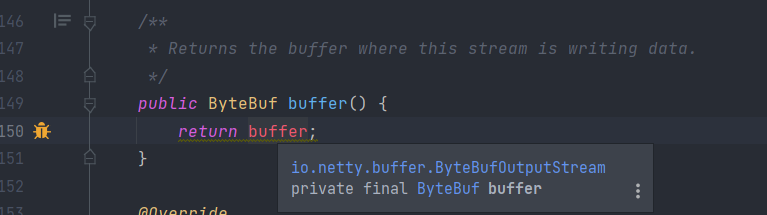

The first one is very insightful. For example in this code, it exposes the private field that could be mutated of the class:

There are other behavior that is intended, like this:

1 |

|

The emptyBuf returned here is thought to be safe. But this variable could be altered and returned again and again to other clients.

Although Netty is a software framework, and that perhaps the only ones having access to those variables are programmers themselves, there still exists the possibility of getting user input from outside world. If one malicious user successfully injects malicious content into the instance of the framework running in application server, there could be server security risk.

“May expose internal representation by incorporating reference to mutable object” is also about misuse of private fields, like this, assigning private Bytebuf buffer a mutable value:

The second category is about general coding style, and therefore is more subjective.

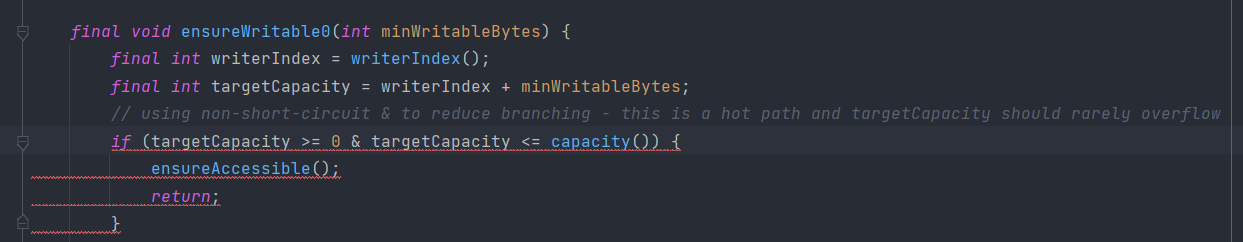

Return value of method without side effect is ignored is often a bad smell of code. If a method with return value is constantly called without using the return value, then there’s high chance that this method violates the single responsibility rule.

1 |

|

But the website of SpotBugs admits that this rule may result in many false positives, and this example is one of them. Actually, checkIndex contains exception-throwing logic:

1 | private ByteBuf checkIndex(int index) { |

So it does have side effects.

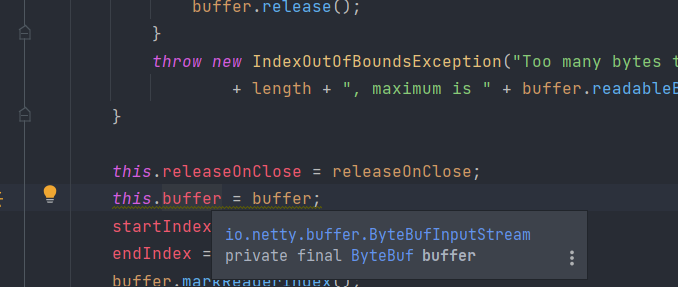

Potentially dangerous use of non-short-circuit logic (e.g. | or &). This rule also indicates a bad smell. In Netty, situations are different, as the case in some of the JDK code: the non-short-circuit logic is used with care in order to gain optimum performance.

This branch is “a hot path” that are executed very often, so Netty chooses to optimize it.

Conclusion and comparison

To sum up, both PDM and SpotBugs reports code style warnings that are useful in most cases. One tool often identifies warnings that are different from the other. For example, the overriding of equals is mentioned by SpotBugs but not by PMD; while PMD finds problems of unclosed resources and suspicious comparisons not using equals. So it could be a good choice to use different static analyzers to get a more complete report.

In terms of code vulnerability, SpotBugs seems to do a better job than PMD both in terms of warning classification and the number of warnings reported. But SpotBugs doesn’t notice the problem of invoking overridable methods from a constructor, even though it does have a rule for it.

As maybe common for static analyzers, the chance of reporting false positive cases are not low. So static analysis is not a silver bullet for code quality check: special care still must be taken by humans.

References

[^1]: What Is Static Code Analysis? – MATLAB and Simulink - MATLAB & Simulink

[^2]: Norman Maurer, Marvin Allen Wolfthal. Netty in Action

[^3]: Error Prone | PMD Source Code Analyzer

[^4]: Effective Java, 3rd Edition